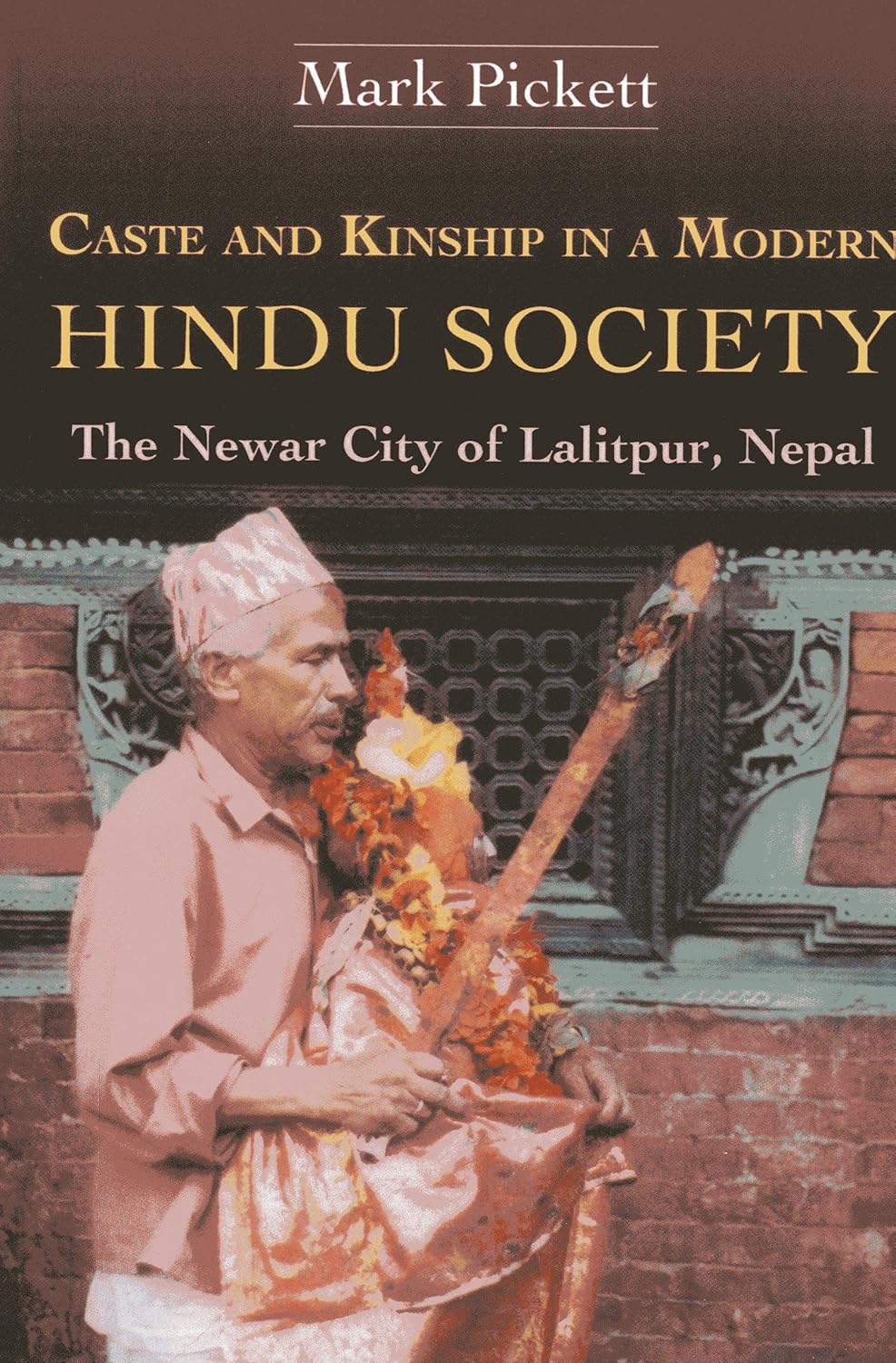

My publisher forgot to include the glossary to my book, Caste and Kinship in a Modern Hindu Society: The Newar City of Lalitpur, Nepal (Bangkok: Orchid, 2013, available here) so here it is for anyone struggling their way through it.

My publisher forgot to include the glossary to my book, Caste and Kinship in a Modern Hindu Society: The Newar City of Lalitpur, Nepal (Bangkok: Orchid, 2013, available here) so here it is for anyone struggling their way through it.

Apart from English terms, all

names and terms are transliterated from Newari, Nepali (Np.) or Sanskrit

(Skt.).

ācārya (ācāḥ)—learned teacher

āgã chẽ—Tantric

shrine

āgã dyaḥ—god that

resides in āgã chẽ

agnate—patrilineal kin, a person

that is related to ego through links with males alone

aĩta—sweet

presented as part of ritual gift-giving

Aji—midwife; provides ritual

service at Birth Purification

Ajimā (Hāriti)—malevolent goddess

Ashtamātrika—Eight Mother

Goddesses

ashtami—Eighth day

of lunar fortnight; important for Buddhists

avatār—‘avatar’;

incarnation of Vishnu

Awāle—Potter

aylaḥ—spirits,

usually distilled from rice

bāhāḥ, bahi—Buddhist monastery

baigaḥ—uppermost

storey of house

bājã—particular

style of traditional music; music in general

baji—beaten

rice, staple at feasts

Bāl Kumāri—one of the Eight

Mother Goddesses

bali—sacrifice,

usually animal

Banepa—small Newar town east of

Bhaktapur

Bārāhi—lineage of Carpenters; one

of the constituent thars of the Pengu

Daḥ

Bhairava—blood-accepting, male

deity; consort of the Devi

bhakta—devotee

(usually in context of Vaishnavite sects)

bhajan—hymn

Bhimsen (Bhindyaḥ)—blood-accepting,

male deity beloved of traders

bhincā macā—sister’s

son and his children

bhoto (Np.)—waistcoat

or vest of Bῦgadyaḥ

bhujyaḥ—offering to

Bῦgadyaḥ

bhutu—hearth

bhway—feast

bodhisattva—one who

aims to become a fully enlightened Buddha

Brahman—a member of a particular

lineage with links to the priesthood

brahman—the

uppermost of the four ideal varna

categories; priest

Bhaktapur—Newar city, east of

Lalitpur

bhusyāḥ—large

cymbals

bhut/pret—ghost,

malevolent spirit

buddhamārgi—a follower

of the path of Buddha; one who has a Vajrācārya domestic priest

Bῦgadyaḥ (coll.)—the god of Bῦga;

Karunāmaya/Matsyendranāth

caḥre—the

fourteenth day of the waning fortnight, especially sacred to the worship of

Shiva.

caitya—votive

Buddhist shrine; like a stupa but

much smaller

cāku—molasses

Cākwāḥdyaḥ (a.k.a. Minnāth)—accompanies

Bῦgadyaḥ on the Jātrā

Caturmāsa—period of four months

of Vishnu’s sleep

chẽ—house

cheli—ground

floor of house

chwāsā—Remains

Deity marked by an aniconic stone embedded in the ground

chwaylā bhu—pre-purification

feast

cibhāḥ—(see caitya)

Citrakār—Painter

cuka—courtyard

cusyāḥ—small

cymbals, accompany naykhĩ

cwatã—second

floor of house

dakshina—ritual fee

dabu—dance

platform

daḥmā—the main

forward beam of the chariot

dāmaru (dabu dabu)—small, one-handed

double-headed drum

dān—inauspicious

gift

dāphā—a genre of

traditional Newar music

darshan—view of the

deity; obeisance

dasa karma—Ten Life-Cycle

Rituals (see samskāra)

Dashmahāvidya—Ten Great

Knowledges; a set of female protective deities

dekhā—Tantric initiation

devi—goddess;

refers to all goddesses or specifically to the great Goddess (the Devi)

Dewāli—season for Lineage Deity

Worship

dhāḥ—two-headed

drum, may be played with wooden stick

dharma—religious

duty, law, custom, classically set out in sacred texts (dharmashastra); by extension, moral order more generally

dhimay—double

headed drum, played with hand and curved cane stick; bigger than dhāḥ

dholi

(Np.)—palanquin

digu dyaḥ—Lineage

Deity

doti—traditional

wrap-around loincloth

dyaḥ—god

dyaḥ pālā—god

guardian; caretaker of a temple

Dyaḥlā—Fisherman/Sweeper

ekadasi—11th

day of lunar fortnight; sacred to Vaishnavites

emic—the perspective of the

insider (the opposite of etic)

galli—narrow lane

Ganesh (Ganedyaḥ)—elephant-headed

god, Shiva’s first son and god of beginnings

ghaḥ—traditional

Newar water pot

Ghaḥku—a lineage of Farmers who

act as brakemen for the Bῦgadyaḥ and Cākwāḥdyaḥ chariots

ghāt—slope,

typically adjacent to a river

ghyaḥ—clarified

butter

Gubhāju (coll.)—Vajrācārya,

Buddhist Priest

guthi (gu)—socio-religious association

guthiyār—member of a guthi

gway—areca

(betel) nut

Haluwāi (coll.)—alternative thar appellation of Sweetmaker or more

general referent of any sweetmaker

hāmwa—sesame

harmin—harmonium

hiti—water spout

Holi—important spring festival

Indra—the Vedic king of the gods

ishtadevatā—chosen

deity

jā—boiled rice

jajmān—patron

jāt/jāti—common term

for group of intermarrying lineages, or caste

jātrā—processional

festival; The Jātrā refers specifically to that of Bῦgadyaḥ

jhyāli—small

cymbals

Joshi—Astrologer

juju—king

Jyāpu (coll.)—Maharjan, Farmer

kacha—raw food

kāshyap (kāshi)-gotra—of Aryan

(Indic) ancestry

Kasāḥ (coll.)—Mulmi/Nyāchyã

Shresthas, Bronzesmiths

kaḥsi—roof

terrace

kalasha—Flask used

for sacred purposes

Kāpāli—Tailor-Musicians

Karamjit—Mahābrāhman death

specialists

Karmācārya (Acāḥju)—Tantric

priest

kartal—two-piece,

one-handed percussion instrument

Karunāmaya—name of bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (see Bῦgadyaḥ)

Kāstakār—Carpenter (alt. to Sthāpit)

Kathmandu—capital city of Nepal;

one of three cities of medieval Nepal Valley

Kãwã—skeletal demon

kawaḥ—sub-lineage

Khadgi (Nay)—Butcher

khaḥ—palanquin

khalaḥ—lineage

khĩ—drum

Khwapa (coll.)—Bhaktapur

khya—the goblin

with the lolling red tongue

khyaḥ—field

Krishna—incarnation of Vishnu

kshatriya—second of

ideal varna categories; warriors and

kings

kuladevatā

(Np.)—Lineage Deity (see digu dyaḥ)

Kumāri—Mother Goddess; also

virgin goddess in Newar societies

Kwenādyaḥ (coll.)—Jala Vināyak;

one of the four important forms of Ganesh in the Valley

lakh—one hundred

thousand

lākha mari—sweet

presented as part of ritual gift-giving

Lakshmi—goddess of good fortune;

Vishnu’s principle wife

Lalitpur—city of Nepal

(Kathmandu) Valley south of Bāgmati River; home of Pengu Daḥ

laptyā bhway—traditional

Newar leaf-plate feast

laskus—ritual

welcome at the door of house or gate of city

lhāsā-gotra—of Tibetan

(Bodic) ancestry

Licchavi—ancient rulers of Nepal

Valley

linga—phallic

representation of Shiva

Lwahãkaḥmi (coll.)—Stonemason;

one of the constituent thars of the

Pengu Daḥ

magaḥ khĩ (Np. mādal)—small two headed drum Mahādyaḥ (Shiva)

Mahālakshmi—Mother Goddess

Maharjan—Farmer

Malla—rulers of medieval Nepal

mānā—volumetric

measure of ten handfuls or about a litre

Mānandhar—Oil Presser

mandala (mandap)—sacred diagram or platform

Marikaḥmi (coll.)—Sweetmaker; one

of the constituent thars of the Pengu

Daḥ

mashān—cremation

ground

mātã—first floor

of a house

melā—grand

festival

mhāy—tenant

mhyāy macā—daughter

and her children

Mohani (Dashaĩ)—the most

important festival of the autumn season

mridanga (Skt.; Nw. pacimā)—two-headed drum

mudrā—ritual

position of the hands

muhāli—shawm

(medieval-style oboe)

Mulmi/Nyāchyã

Shresthas—Bronzesmiths

murti—image or

form of deity

nāga—serpent

deity

Nakaḥmi—(Newar) Blacksmith

nakhaḥ—festival

nakhaḥtyā—feast

associated with a nakhaḥ

Narasimha—‘man-lion’ incarnation

of Vishnu

Nārāyana—alternative name of

Vishnu; common form in Nepal

nani—courtyard

Nāpit (Nau)—Barber

Nauni—Barber’s wife

nāyaḥ—supervisor

naykhĩ—double-headed

drum, like dhāḥ but smaller; usually

played by Butchers (Nay)

nitya pujā—daily

worship

Nyāchyã—(see Mulmi)

Panauti—small Newar town in

Banepa Valley

pāju—mother’s

brother

Pānju—priest of Bῦgadyaḥ

Parbatiyā—Nepalese of the hills

pāthi—volumetric

measure equivalent to eight mānās

Pengu Daḥ— ‘The Four Groups’; the

focus of this study

phālca—public

shelter

phuki—patrilineal

relative

pikhā lakhu—carved stone

that marks the ritual entrance to the house; Kumar

pitha (pigandyaḥ)—Power-Place

pitri—ancestor

pradakshinapātha

(Skt.)—procession route

Prahlāda—son of Hiranyakashipu;

devotee of Vishnu

prākrit—natural,

aniconic stone image

Pramānas—medieval, de-facto

rulers of Lalitpur

prasād—‘grace’;

sanctified food, flowers and sinha

distributed to worshippers in return for pujā

pujā—worship,

usually comprising offerings of fruit, flowers, vermilion, and sweets

pujāri—temple

priest

pukka—food that

has been made acceptable to eat; well cooked; more generally, solid

purohit—domestic

priest

punhi—full moon,

auspicious day especially for Buddhists

pwanga—short horn

pyākhã—dance-drama

Rādhā—Krishna’s lover

Rājbhandāri—Royal Storekeeper,

member of dominant caste

Rājopādhyāya—Newar Brahman caste

Rājkarnikār (Marikaḥmi)—Sweetmaker

Rām (Rāma)—avatar of Vishnu

Rana—rulers of Nepal from

1847-1951

sadhu (see sannyasin)—ascetic renouncer

sagã—good luck

food; two varieties-egg (khẽy) and

fish (nyā)

sāit—auspicious

time

samay baji—feast-like

meal consumed after special pujā

Samgha—Buddhist Monastic

Community

samskāra—life-cycle

rituals

Sankhu—small town north of

Bhaktapur

sãnhu (sãlhu)—first day of solar month

sannyasin—ascetic

renouncer

Sarasvati—goddess of learning,

Brahma’s wife

Shaivite—of, or pertaining to,

Shiva; worshipper of Shiva

Shah—present dynasty of Nepal

kings; descendants of Prithvi Narayan Shah

Shākya (Bare)—Goldsmiths; also

workers of silver and brass; shopkeepers; of one caste with Vajrācāryas

Shilākār (Lwahãkaḥmi)—Stonemason;

alt. thar appellation for Shilpakār

Shilpakār (Lwahãkaḥmi or Sikaḥmi)—Sculptor

shivamārgi—a follower

of the path of Shiva; one who has a Brahman priest

shudra—fourth of

ideal varna categories; servants,

slaves, labourers

Sikaḥmi (coll.)—Carpenter; one of

the constituent thars of the Pengu Daḥ

sinha—mark of

vermilion on forehead

shakti—divine

power, personified as feminine

shawm—medieval-style oboe

shrāddha—Ancestor

Worship

Shrestha—dominant Newar caste;

proper thar name of some of these

sikāḥ bhu—meal

involving ritual division of head of sacrificial animal

sinājyā myẽ—rice

transplantation song

snāna—ritual

bathing

soḥra shrāddha—Sixteen

[Day] Ancestor Worship

Sthāpit (Sikaḥmi)—Carpenter

stupa (thur)—sacred mound

Swanti (Np. Tihār)—important

late-autumnal festival

syāḥ phuki—close or

‘bone marrow’ kin

tāḥ—bells

taksāri—chief of

royal mint

Taleju—chosen deity of Malla

kings; blood-accepting female deity

Tamvaḥ (coll.)—Coppersmith; one

of the constituent thars of the Pengu

Daḥ

Tāmrakār (Tamvaḥ)—Coppersmith

tāpā phuki—distant kin

thaḥ chẽ—natal home

of married woman

thākāli—senior

male; elder

thākāli luyegu—initiation

as a thākāli

thākāli nakĩ—senior

married female

thar—surname

thāy bhu—ceremonial

dish used at a Marriage or Mock Marriage celebration

Theravāda Buddhism—form of

Buddhism found in Sri Lanka and more recently brought to Nepal

thon—homebrewed

beer

thyasaphu—biographical

entry on a legal document

trope—a word or expression used

in a figurative sense

Tulādhar—principle thar of merchant caste in Kathmandu

tulasi—sacred

basil plant; worshipped as Vishnu throughout Caturmāsa

twaḥ (Np. tol)—traditional locality

Urāy (coll.)—Tulādhar et al.

utsāva (Skt.)—festival

vaikuntha—Vishnu’s

abode

Vaishnava (Vaishnavite)—of or

pertaining to Vishnu; worshipper of Vishnu

vaishya—third of

ideal varna categories; traders

Vajrācārya—Buddhist Priest

Vārāha—the boar-avatar of Vishnu

varna—‘colour’;

system of castes in sacred texts; ideal caste structure

vermilion—mercuric sulphide; a

bright red to reddish-orange coloured powder; mixed with curd, and husked rice

it is applied with the finger to the image of the deity and thence to the

worshipper’s forehead as prasād

Vishvakarma—patron deity of

artisans

vrata—Observance

including fasting usually in devotion toward a particular deity

waḥ—lentil cake

wala pala or wala pā—sub-section of guthi

yaḥ—festival

yaḥ mari—special

rice cake especially consumed at winter solstice festival

yaḥsĩ—ceremonial

pole

yajña (homa)—Fire Sacrifice

yaksha—demon

Yama (Yamadyaḥ, Yamarāja)—the god

of the abode of the dead

Yāngwa—a lineage of Farmers who

lash the chariot together with vines

Yẽnyaḥ (Indra Jātrā)—important

late-monsoon festival